Patriachies in both the countries have been subjected to strong cross-cultural currents for centuries together. However, Confucianism in China and Brahminism manifested in the Manusmriti in India treat women with discrimination which are dominant idiologies. Of course, Buddhism preaching equality between sexes did prevail in both the countries but have only a tangential impact on the patriarchy.

In the present century both the countries have undergone catalytic events namely the Freedom Struggle in India and a Political Revolution in China which tried to include women in the mainstream of those events. With the introduction of Structural Adjustment Programmes in both the countries some of the feudal values have reemerged, though it is our contention that the situation will not slide back to the original dark age due to the presence of the women’s movement and awareness among men and women. In the subsequent sections we will discuss the social and economic status of both the countries to show that the Chinese women are a shade better than their counterparts in India.

Social Status of Women

India: The family and society at large consider women as second class citizens. The rituals relating to birth and marriage reflect a son-preference.1. A related phenomenon of son-preference in the modern context is the amniocentesis test to abort the female feolus. This unfortunately is more prevalent in urban India. The sex selective test has increased the male-female ratio between 1981 and 1991 in a significant manner (Murthi, Guio & Dreze, 1997). The prevalence of dowry has increased a great deal and has spread to the low caste groups which earlier practised bride price. So much so that the ideal Kerala practice of husbands staying in wiv9s houses has changed to demanding dowry. This phenomenon of takingdowry has increased considerably after the young men started going to Gulf countries and needed a lot of money to buy tickets and other things. Another important point with regard to marriage practices is that the majority of the marriages are arranged by parents. Love marriages are not encouraged even in urban areas though acute violence against women in recent years compel the parents not to consider arranged marriages particularly in the metropolitan cities like Delhi and Bombay etc. The assumption that the urban population are more modern in outlook and hence the traditional bias would get reduced there is proved wrong.

Other indicators of slow changing social mores are the characteristics of matrimonial columns of the leading English dailies, and advertisements in other media. For example the majority of the matrimonial ads show the preference of brides from the same castes and should absolutely be of fair complexion. The same bias for fair complexion also gets reflected in the range of cosmetic and more specifically a brand of face cream called “fair and lovely”. It seems that the sale of this brand of cream gets sky rocketed just before the onset of the marriage season. If this is so in the urban areas it would be even truer in the rural areas.

In spite of Sharda Act which was passed in the 1950s to raise the age at marriage, child marriage particularly in North India is quite prevalent though the average age at marriage for females has increased to 18. Child marriage gives a very long span of reproductive age telling upon the health of the women as we will see a little later. This also gets reflected in terms of intra-family distribution of food, access to basic education and health care.

In the 1970s there was a discourse on whether women get adequate nutrition according to their needs or are they discriminated against. Some felt that women do sedentary work and hence require less calories. However, if we examine the work schedules of both men and women it is noticed that women are working for longer hours than men. But according to social norms they get less food.

In so far as access to health care also generally women do not get the best treatment when they fall ill. In addition the consciousness of being ill is more manifest among men than among women who always voluntarily suppress their ailment. (Kynch and Sen, 1983).

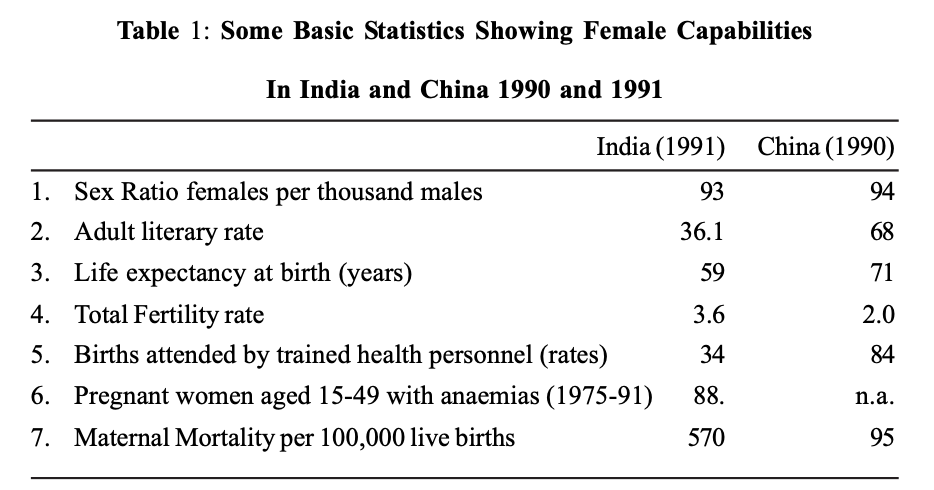

The size of average household has marginally declined from 5.55 to 5.51 in the last decade with a sharp decline in urban India during the same period indicating a high fertility and son-preference in the rural area particularly in North India. The total fertility rate for India as a whole is 3.7 in 1991.

The large size family shows that parents live with married sons since facilities are few for old age homes and taboos are attached if the parents stay separately or with married daughters. While it is important to look after old people, it is also true that in-Iaws interfere in every sphere of life of the daughters-in-Iaw. As a result the norms of having large families, son-preference, discriminating attitude towards daughters get perpetuated.

On the front of literacy the picture is equally bleak. As per 1991 census only 39 per cent of the women population are literate. In other words more than 60 per cent women are still illiterate reflecting the low priority given to female literacy. The per centage of illiteracy is much higher (64 per cent) in the older age groups.

Another important pointer towards the discrimination against female child is the increasing sex ratio (males per 1000 females) over these years, in the age group of 0-6 years even though the child mortality rates for males and females in the age group of 0-4 years have narrowed down in the eighties. The explanation as alluded to earlier, lies in the fact that selective abortion is taking place in the urban areas of almost all the states. (Raju and Premi 1994).

In other age groups also women do not fare well compared to Chinese women. For example the maternal mortality rate is quite high in 1990 amounting to 570 per 100,000 births (Human Development Report, 1997), one of the contributory factors being only twenty per cent of the births are attended by the health personnel even as late as 1990.2.

Generally women live longer than men after the reproductive age is over. Coupled with that the total fertility has declined. Hence the life expectancy at birth for females shows a shade higher than that of males, being 61.4 and 61.1 years respectively in 1994 (Human Development Report, 1997). However, the full potential of biological advantage accrue to women especially after the reproductive age has been denied to Indian women partly because a majority of women deliver their babies at home in North India and do not get best medical treatment when they are ill. (6reze and Sen, 1995). Thus we find that the social status of women in India, though with regional variations, is low as indicated by the indices like high sex ratio, high maternal mortality, low literacy rate etc.

Economic Status in India

>

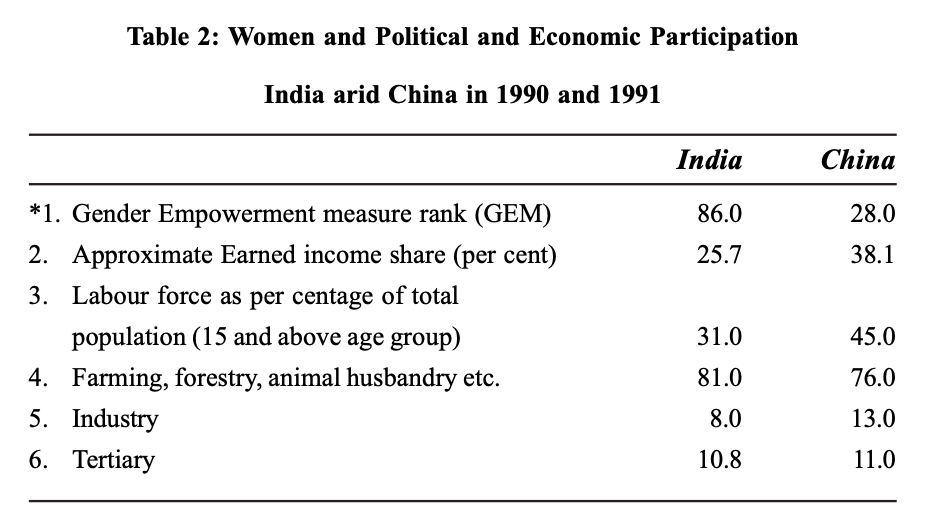

Low social status of women gets reflected in low economic status also. We have noticed before that about 61 per cent of the Indian women are illiterates as per 1991 census. Accordingly, most of the women work in unorganised sector either in agriculture or in household industries. This in turn does not get captured in “statistical purdah” created by existing concepts and the methods of measuring labour participation that creates invisibility of women’s contribution to National Income of the country (Gopalan, 1995). For example, the census defines work as gainful economic activities but activities done for domestic consumption are not considered as work. So we find that as late as 1991 only 22 per cent of total female population are considered to be workers in contrast to 52 per cent of the male population though the rural areas show slightly higher female work participation rate namely, 27 per cent, than that of the total rate. As expected the urban area has failed to provide much avenues for female workers as is evident from the statistics. (Premi and Raju, 1994).

In this context it is interesting to note that the recorded female participation rates varied across the states inversely with the influence of dominant patriarchal values except perhaps in Kerala. For example Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Punjab and Haryana recorded female participation rates much below than the national average namely 22 per cent. But the states like Mizoram, Meghalaya, Manipur recorded much higher rate i.e., above 35 per cent which are not influenced by the patriarchal values of the North. Also Maharashtra which has undergone several social movements and is witnessing a different pattern of development compared to Punjab and Haryana has 33 per cent female work participation rate in 1991.6.

Sectoral division of work participation rate is also available from various sources. For instance, in 1981 about 94 per cent of female work force and 89 per cent of male work force was working in the unorganised sector” In 1991 on the other hand the share of male work force has increased by 1 per cent whereas that of female work force has increased by two per cent. (Gopalan, 1995)

The Census also gives nine-fold classification of main workers in different industrial categories which can be further aggregated into primary, secondary and tertiary activities. The most important feature of this classification is that about 81 per cent of the total female workers are engaged in primary sector consisting of agriculture, live stock and mining in 1991. This per centage is very high in rural area namely 89.5 per cent which shows a marginal increase as compared to the 1981 situation. In contrast the per centage of male workers in the primary sector is 63.4 in 1991 and lower than that of females in rural areas by 8 per cent (Premi and Raju, 1994). It should also be noted that the per centage of male workers in the primary sector has declined between 1981 and 1991 and that of service sector has increased. But in case of female workers there has been a ‘1eminisation” of primary sector. Several explanations have been offered to analyse this phenomenon. First of all, the Green Revolution has created some opportunities for women in agriculture. Secondly, the growing middle class has withdrawn male children from work and is sending them to schools leaving behind the girl child to slog in the field. Finally, whenever development generates more lucrative job opportunities, the men workers try to grab it first. With regard to the female industrial work force we notice another feature. The National Sample Survey Organisation has detailed industries into 384 divisions. It is interesting to find that women workers concentrate only in a few industries such as rearing of poultry, manufacturing of beedies (indigenous coarse cigarettes), matches and cotton spinning etc. all in the low skill and low paid categories. (Gopalan, 1995)

Since the female literacy rate is low (39 per cent in 1991), the per centage of women employees in Central and State governments is much lower than that of men (the per centage being 7.50 and 34.91 respectively in 1990). (Gopalan,1995)

The gap between male and female wage rates show that for the same type of work women workers get lower rates vis- a-vis men workers. For example a male construction worker gets Rs. 31.58 per day but a female worker gets Rs.18.27 in a rural setting. The gap however, narrows down slightly in the urban area but it is still too glaring. (Gopalan, 1995). However, it is to be mentioned that different state governments have passed laws to give equal wage rates for men and women for doing similar kind of work. With regard to the impact of Structural Adjustment Programmes on Women’s Work which was introduced in 1990, no systematic study has been done. But most of the women work in the unorganised sector. It is likely that in some cases their demand for certain specific activities such as electronic goods may increase. But in other cases they will be eased out first, if recession sets in the economy. More lucrative jobs will be taken up by men and market may perpetuate unequal status for women.

Thus we notice that the low status of women in the society gets reflected in low status of employment opportunities which gets reinforced by lack of land rights to women in India. In the next section we will see how have the Chinese women fared in so far as the economic empowerment is concerned.

Sources:

1. Richard Jolly (1997) Human Development Report (Oxford University Press, New Delhi).

2. J. Dreze and A. Sen (1995) India: Economic Development and Social Opportunity. (Oxford University Press Delhi).

*Gender empowerment measure rank is calculated taking women parliamentarians, administrators and managers, professional and technical workers and earned income share. So lower the value higher the rank. However if we include the women in politics at the grassroots level with 33.3 per cent reservation, the rank of India’s GEM will increase.

Sources:

1. Human Development Report, 1997.

2. M.K. Phemi and S. Raju (1994) Gender in work force participation in the 1991 in India. Submitted to UNIFEM (Unpublished).

3. Department of Social Science and Technology Statistics State Statistical Bureau (1995) Women and Men in China: Facts and Figures (Statistical Bureau, PRC Beijing).

WASHINGTON, May 14, 2014—Girls with little or no education are far more likely to be married as children, suffer domestic violence, live in poverty, and lack a say over household spending or their own health care than better-educated peers, which harms them, their children, and communities, a new report by the World Bank Group finds.

Some 65 percent of women with primary education or less globally are married as children, lack control over household resources, and condone wife-beating, compared with 5 percent of women who finish high school, Voice and Agency: Empowering Women and Girls for Shared Prosperity finds.

The report distills vast data and hundreds of studies to shed new light on constraints facing women and girls worldwide, from epidemic levels of gender- based violence to biased laws and norms that prevent them from owning property, working, and making decisions about their own lives.

Across 18 of the 20 countries with the highest prevalence of child marriage, girls with no education were up to six times more likely to marry than girls with high school education, it finds. Nearly one in five girls in developing countries meanwhile becomes pregnant before age 18, while pregnancy-related causes account for most deaths among girls 15-19 in the developing world—nearly 70,000 die each year.

“The persistent constraints and deprivations that prevent many of the world’s women from achieving their potential have huge consequences for individuals, families, communities, and nations,” World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim said. “Expanding women’s ability to make decisions and take advantage of opportunities is critical to improving their lives as well as the world we all share.”

“If the world is going to end extreme poverty and ensure that prosperity is shared by all, we have to have the full and equal participation of women and men, girls and boys, around the world,” Kim said. He launched the report here today with Former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and UN Women Executive Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka.

Despite recent advances in important aspects of the lives of girls and women, pervasive challenges remain, frequently as a result of widespread deprivations and constraints. These often violate women’s most basic rights and are magnified and multiplied by poverty and lack of education.

In all regions, better educated women tend to marry later and have fewer children. “Enhanced agency—the ability to make decisions and act on them—is a key reason why children of better educated women are less likely to be stunted: Educated mothers have greater autonomy in making decisions and more power to act for their children’s benefit,” World Bank Group Director for Gender and Development Jeni Klugman said. “Educated mothers have greater autonomy in making decisions and more power to act for their children’s benefit.”

In Ethiopia, one-year-olds whose mothers had a primary school education along with access to antenatal care were 39 percent less likely to have stunted growth, for example, while in Vietnam infants whose mothers had attained a lower- secondary education were 67 percent less likely to have stunted growth.

Voice and Agency, which builds on the 2012 World Development Report, focuses on several areas key to women’s empowerment: freedom from violence, control over sexual and reproductive health and rights, ownership and control of land and housing, and voice and collective action. It explores the power of social norms in dictating how men and women can and cannot behave—deterring women from owning property or working even where laws permit, for example, because those who do become outcasts.

In 128 countries, laws treat men and women differently—making it impossible, for example, for a woman to independently obtain an ID card, own or use property, access credit, or get a job.

Key facts:

• Gender-based violence is a global phenomenon, and in most regions no place is less safe for a woman than her own home: More than one in three women have experienced violence, the vast majority committed by their husbands or boyfriends. That’s 700 million women—close to the total population of Sub-Saharan Africa.

• Girls are increasingly completing school and university, but their work choices remain restricted, by laws and/or social norms that dictate whether and what work is appropriate. Foregone costs in terms of productivity and income can be huge. Many women lack sexual and reproductive rights: Data from 33 developing countries reveal that almost one third of women cannot refuse sex with their partners—rising to more than seven out of 10 Nigerian, Malian, and Senegalese women—and more than 41 percent across those 33 countries say they could not ask their partner to use a condom.

• Each year, almost one in five girls under 18 in developing countries gives birth: South Asia accounts for almost half of teen pregnancies in the developing world. In developing countries, pregnancy-related causes account for most deaths among girls aged 15-19—nearly 70,000 die each year. The lifetime opportunity costs of adolescent pregnancy, measured in terms of lost income, range as high as 30 percent of GDP in Uganda.

• Women and girls face a major gap in access to and use and ownerships of ICT. In Sub-Saharan Africa, 32 million fewer women have access to the Internet than men. In South Asia, 25 million fewer women have access, and in the Middle East and North Africa, 18 million.

• Poverty increases gender gaps: Girls living in poor households are almost twice as likely as their richer peers to marry young. Intimate partner violence is also more frequent and severe in poorer households across such diverse settings as India and Nicaragua.

• Women’s groups and collective action play a pivotal role in building momentum for progressive reform. Strong women’s movements are associated with more comprehensive policies on violence against women. And when more women are elected to office, policy-making increasingly reflects the priorities of families and women and results in greater responsiveness to citizen needs.

Urgent Agenda

Policymakers and stakeholders need to tackle this agenda, drawing on evidence about what works and systematically tracking progress on the ground. This must start with reforming discriminatory laws and follow through with concerted policies and public actions, including multi-sectoral approaches that engage with men and boys and challenge adverse social norms.

Expanding opportunities and amplifying the voices of women and girls isn’t a zero-sum equation, because gender equality conveys broad development dividends for men and boys, families, and communities. Conversely, constraining women’s agency by limiting what jobs they can do or condoning gender-based violence can cause huge economic losses and hinder development efforts.

Increasing school enrollment and achieving gender equality in enrollment are longstanding development goals. Ensuring enrollment through upper secondary levels for girls is even more critical. Equally vital is what happens at school: Both girls and boys leave school literate and numerate and that the values of the school system promote gender equality and protect children from abuse.

Progress on the sexual and reproductive health front tends to involve multi- sectoral actions: access to contraception is critical, alongside raising awareness, life skills training, mentoring and peer group training, and activity clubs and sports.

Women’s land rights—which support women’s agency—can be strengthened by progressive legal reforms and improved governance. Mandatory joint-titling helps and statutory, customary, and religious regimes should be harmonized, with clear consent requirements for land transfer or sale.

More and better data are needed to measure progress and to hold governments and development agencies, such as the World Bank, to account.Recently agreed international Core Gender Indicators are a valuable basis, alongside agreed statistical indicators and guidelines for measuring violence against women. More rigorous evaluations of what works are also needed, particularly around collective voice, normative change, and program design, the report says.

Conclusion:

Both China and India situated on both sides of the Himalayas have experienced centuries old civilisations with underlying partriarchal ideas. The present century witnessed two catalytic events in India and China which tried to involve women in the mainstream. In India however, the post-independent government did not make sustained effort to visibly enhance women’s contribution. As a result, after the freedom movement was over women were still treated as second class citizens. Even after the anti-dowry laws were passed the incidence of dowry death has still been on the increase. Son-preference, has still dominated the Indian psyche. Women are still discriminated against with regard to access to food and health care. The sex ratio over the years has increased and reached the highest point of 107 in 1991. Similarly the low status of women and girl child got reflected through low literacy rate.

In India, the reality of the low social status of women, evidently prevents their work from getting its due value. The total work participation rate of females in 1991 is only 22.27. In rural areas it is slightly higher namely 26.79 than the total rate. Sectoral distribution indicated that 95 per cent of the female workers are concentrated in agriculture although the service sector also absorbed more women than the manufacturing sector which is the least women-friendly. As expected the wage rates for equal amount of work are not the same for males and females. But one positive thing has occurred in India namely women’s movement which started in 1975. It not only has changed the academic curriculum at the university level, but also has influenced the policy perspective of the government leading to 33 per cent seat reservations in the local level political institutions along with other things. This in turn has brought about one million women to public life for the first time.

In contrast to the Indian situation, the political revolution of 1949 in China created situations in which the social and economic roles of women were much sought after. The leadership’s resort to breaking the feudal values created a frontal attack on the bastion of such values namely, the family. As a result, grudgingly though, the patriarchal regime conceded some ground. The Marriage Law of 1950 was passed which raised the age of marriage and put emphasis on the mother’s and child’s health. The maternal mortality declined. Literacy increased. Women’s participation in economic activities increased considerably.

Like the nine lives of the cat, the patriarchal regime bounced back after the reforms had started. Women could not get out of the agricultural sector and made only a modest gain in the service sector. Because of the one child policy female infanticide particularly in the rural areas have started reappearing. Women workers are most vulnerable to retrenchment. They do not enjoy equal pay for equal work. Their retirement age is lower than that of men though their life expectancy is higher than men by four to five years.

Unlike India, the interventions through women’s movement started very late i.e., after 1990 though the oldest women’s organisation (All China Women’s Federation) came into being in 1949. After 1990, the women study centres have been set up in different universities and have taken up the gender issues more actively. Thus we find the status of Chinese women better than that of Indian women though both the sister countries have to take long journey before they reach the goal of equality and justice.

References

• China Association for Labour Studies (1995). Woman and Employment in China. (Beijing).

• Chinese Government’s White Paper on Women {1994). Reproduced in China Report {1994) 30: 4.

• Das Gupta, Monica Jiang Zhenghua Xie Zhenmlng L, Bohua (1997) “The status of Girls in China: in 231d IUSSP General Populalion Conference Symposium on Demography of China, China Population Associabon Beijing, 1997.

• Dreze, Jean and Sen, Amartya (1995). India Economic and Social Development (Oxford, University Press Delhi” Government 01 India (1995) Country Report prepared on tile eve of Fourth World Congress of women, Beijing (Department of Woman and Child Development New Delhi”

• Gopalan, Sarala. Women and Employment in India, Har-Anand Publications, Delhi 1995.

• Gulati, L and Rajan, l ‘Gender issue in work force pa”,clpat”n on Kerala’ unpublished state report for IASP -UNIFEM Project on Gender Issues in 1991 Census Thiruvananthapuram CDs 1993.

• Jolly, Richard, Human Development Report Oxford University Press, New York 1997.

• Kynch Jocelyn, and Sen Amrtya ‘Indian Women Well-being and Survival”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 7, 1983.

• Li, Chen9nJi, A study of Chinas population, Foreign Lan9uages Press Beijing, 1992.

• Lin Fude and Liu Jintang ‘Chinas Fertility Transition and tile Prospect of Population Situation’ 1997 in 23rd IUSSP General Population Conference, Symposium on Demography of China, China Populatlion Association, Beijing, 1997.

• Mohanty, Bldyut ‘Women and Panchayati Raj and Seventy Third Amendment Act’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol52 1995.

• Murthy Mamta Guio Anne Catilerine and Dreze, Jean ‘Mortally Fertility and Gender Bias in India A district level analysis’ in Sen, A and Dreze J (ed) Indian Development Selected Regional Perspective, Oxford University Press Delhi,1997.

• Premi, MK and Raju, Saraswab (1994) Gender issues in work force participation in the 1991 Census in India A repo” submitled to UNIFEM (Unpublished).

• Rai, S ‘Gender Issues in China A Survery”, China Report, Vol 30, No 4, 1994.

• Raju, S and Pre.;, MK ‘Decline in Sex Ratio: Alterative Explanation Reexamined”, Economic and Political Weekly, April 2S, 1992.

• Ritu Agarwal, Gender Justice and Economic Reforms In India and China A Study of the Country Papers Presented at the Fourth World Congress on Women in Beijing, M phil Thesis submitted to Delhi University (unpublished”

1997.

• Sha, Jicai and Xiong Yu ‘An Analysis on Family status 01 Contemporary Chinese Women\ in Symposum, 1997.

• State Statistical Bureau Women and Men in China facts and figures China Statistical publishing House, Beijing 1995.

• Human Development Report, 1997

• M.K. Phemi and S. Raju (1994) Gender in work force participation in the

1991 in India. Submitted to UNIFEM (Unpublished).

• Department of Social Science and Technology Statistics State Statistical Bureau (1995) Women and Men in China: Facts and Figures (Statistical Bureau, PRC Beijing).